The global commercial baking industry stands at a pivotal juncture, confronting a perfect storm of converging pressures that are fundamentally reshaping the economics of production. Persistent and systemic labor shortages are straining operational capacity, while volatile and escalating energy costs are eroding already thin margins. Simultaneously, a new era of regulatory scrutiny, particularly in the European Union, is imposing stringent standards for energy efficiency and environmental impact, moving sustainability from a corporate ideal to a non-negotiable baseline for market access. Compounding these operational challenges is an increasingly sophisticated consumer base. Today’s market demands not only convenience and value but also a diverse and ever-changing portfolio of products characterized by artisan quality, clean labels, functional health benefits, and bold new flavors.

This complex landscape demands more than incremental improvements; it requires a paradigm shift in how bakeries operate. The technological response to these pressures is a suite of ten interconnected innovations that are poised to define the state-of-the-art in 2025. These are not isolated gadgets or standalone machines but rather the foundational components of a new operational philosophy: the autonomous, sustainable bakery. This report provides a strategic analysis of these ten innovations, moving beyond technical specifications to explore their business impact, key market players, regulatory context, and return on investment. The central thesis is that the adoption of these technologies is no longer a discretionary choice for achieving a competitive edge but a strategic imperative for long-term survival and growth.

The innovations detailed herein represent a transition from reactive problem-solving—addressing quality issues after they occur, managing downtime as it happens—to a proactive, data-driven model of predictive optimization. They form a synergistic system where AI-powered intelligence, holistic automation, resource efficiency, and product versatility converge. From ovens that learn and adapt with every bake to fully integrated IoT ecosystems that manage the entire production line, these technologies empower bakeries to produce higher-quality products with unprecedented consistency, all while minimizing labor dependency, reducing waste, and slashing energy consumption. This document serves as a comprehensive roadmap for industry leaders to navigate this transformation, enabling them to make the informed investment decisions necessary to build the resilient, profitable, and future-proof bakery of 2025 and beyond.

Table 1: 2025 Innovation & Technology Matrix

| Innovation Number & Title |

Core Function |

Primary Business Benefit |

Key Manufacturers/Technology Providers |

Primary Target Bakery |

| 1. AI-Powered Oven Intelligence |

Real-time, adaptive process control |

Energy & Waste Reduction, Quality Consistency |

Bosch, AMF Bakery Systems, Middleby, Siemens |

Industrial, In-Store |

| 2. Integrated IoT Ecosystem |

Centralized plant-wide data management & control |

Holistic Efficiency, Predictive Maintenance, Traceability |

Grantek, WP Bakery Group, AMF, Bühler Group |

Industrial |

| 3. Collaborative Robotics |

Automation of manual handling tasks |

Labor Optimization, Ergonomic Safety, Consistency |

Universal Robots (Integrators), FANUC (Integrators) |

Industrial, Artisan |

| 4. Hybrid & Hydrogen Thermal Systems |

Flexible, low-carbon energy utilization |

Decarbonization, Energy Cost Hedging |

AMF Bakery Systems, Bühler Group |

Industrial |

| 5. Advanced Heat Recovery |

Capture & reuse of waste process heat |

Direct Energy Cost Reduction, EU Compliance |

WP Bakery Group, WACHTEL, Exodraft, Revent |

Industrial, Artisan |

| 6. Automated Cleaning (CIP) |

Automated, resource-efficient sanitation |

Increased Production Time, Food Safety Assurance |

Solenis (Diversey), Korutek, Colussi Ermes |

Industrial |

| 7. In-Line NIR Spectroscopy |

Real-time, non-destructive quality analysis |

Zero-Defect Production, Reduced Waste |

Polytec, ScanRG, Brabender/Anton Paar |

Industrial |

| 8. High-Yield Soft Dough Lines |

Gentle, automated handling of high-hydration doughs |

Premium Product Scalability, Quality Enhancement |

FRITSCH (MULTIVAC), RAM SRL |

Industrial |

| 9. Modular, Multi-Zone Ovens |

Flexible, multi-product baking in a single unit |

Product Versatility, Space & Energy Efficiency |

WACHTEL, WIESHEU, MIWE, Sveba Dahlen |

Artisan, In-Store |

| 10. High-Speed Vacuum Cooling |

Rapid post-bake product cooling |

Throughput Amplification, Reduced Footprint |

WP Bakery Group, Revent, C-Tech (Research) |

Industrial |

Part I: The Digital Transformation of the Bakehouse

The modern bakery is evolving from a collection of standalone machines into a smart, interconnected organism. The innovations in this section represent the “brain” and “nervous system” of this new entity, leveraging data, artificial intelligence, and robotics to create a self-aware, self-optimizing production environment that transcends the limitations of manual control and siloed automation.

Innovation 1: AI-Powered Oven Intelligence & Predictive Baking

The evolution of the bakery oven is undergoing its most significant transformation in decades, marking a definitive leap from automation to true autonomy. For years, programmable logic controllers (PLCs) have enabled ovens to follow pre-set commands with high fidelity. However, the innovation poised to define 2025 is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which allows the oven not merely to follow a recipe, but to learn, adapt, and predict the perfect bake in real-time.

Core Technology

At the heart of this innovation is a synthesis of three key technological pillars. First, AI algorithms and machine learning models form the cognitive core of the system. Instead of relying on fixed time and temperature settings, these ovens analyze vast datasets to determine the optimal baking parameters dynamically. The Bosch Series 8 oven serves as a market-leading example; it is equipped with sensors that collect anonymized data on every baking process, including temperature, humidity, and user settings. This data is transmitted to a central cloud, where an AI analyzes it to calculate the ideal cooking time for each specific dish, continuously refining its predictions with every bake.

Second, this intelligence is fed by an integrated suite of advanced sensors. These are the oven’s sensory organs, providing the rich, real-time data the AI needs to make informed decisions. Internal sensors constantly monitor critical variables such as internal humidity, dough consistency, browning color, and even product texture, moving far beyond simple temperature probes. This constant stream of data allows the oven to adjust its operation on the fly, compensating for minor variations in ingredients or ambient kitchen conditions that would otherwise lead to inconsistent results.

Third, cloud connectivity creates a powerful network effect. Each individual oven does not learn in isolation. As described in the Bosch model, every bake contributes to a growing global database. This means that an oven in a bakery in Düsseldorf benefits from the collective experience of thousands of other connected ovens around theworld. This shared intelligence accelerates the learning process exponentially, allowing the system to master new products and adapt to new recipes with remarkable speed and accuracy.

Key Players & Systems

Several leading manufacturers are at the forefront of this technological shift, each offering a unique platform that embodies the principles of AI-powered baking:

- Bosch: The Series 8 oven is a clear pioneer, explicitly leveraging cloud-based AI to learn from user preferences and anonymized baking data to perfect outcomes for the entire network of connected appliances.

- AMF Bakery Systems: Through its AMFConnect™ platform, AMF offers a Sustainable Oven Service (SOS). This service utilizes key performance indicators (KPIs) such as occupancy rates, baking conditions, and eco-efficiency to benchmark and continuously optimize oven performance, turning data into actionable insights for energy reduction and quality improvement.

- Middleby Corporation: The company has launched IoT-enabled conveyor ovens featuring predictive maintenance capabilities, which use data to forecast potential failures before they occur. This is complemented by their Open Kitchen platform, which incorporates an AI-driven feature called “DemandSmart” to actively manage and reduce peak energy consumption across connected equipment.

- Siemens: The Home Connect platform, integrated into Siemens’ smart ovens, includes an “Oven Assistant.” This feature allows users to describe the dish they want to cook, either via the app or voice command, and the AI recommends the ideal program and settings, which are then sent directly to the oven.

Impact Analysis

The business implications of AI-powered ovens are profound and multifaceted, addressing several of the industry’s most pressing challenges.

- Unprecedented Consistency: By dynamically adjusting to real-time conditions, these ovens can produce a perfectly consistent product, batch after batch. This eliminates the subtle variations caused by fluctuating ambient humidity, minor differences in flour protein content, or operator-to-operator discrepancies, achieving a level of quality control that is humanly impossible to sustain over long production shifts.

- De-skilling Critical Operations: The baking industry is facing a severe shortage of skilled labor, particularly experienced “master bakers” who possess the intuitive knowledge to manage ovens effectively. AI-powered ovens democratize this expertise. They embed decades of baking knowledge into their algorithms, allowing less experienced or semi-skilled operators to achieve master-level results with minimal training. The WP Kemper KRONOS digital mixer exemplifies this principle, using its “implanted expert knowledge bank” to determine the optimal mixing time and deliver reproducible dough quality regardless of operator experience. This significantly mitigates the risk associated with labor volatility and high turnover.

- Radical Energy & Waste Reduction: The AI’s primary function is to achieve a perfect bake using the minimum necessary resources. Smart ovens can automatically shut off the moment a product reaches its target core temperature or desired color, preventing over-baking. This proactive control drastically reduces both energy waste from unnecessary heating and product waste from discarded, over-baked goods. This directly addresses the systemic inefficiency of running ovens for fixed times, which often includes a “safety margin” of extra time and energy to account for process variability.

The emergence of AI-powered ovens is driving a fundamental restructuring of the business relationship between bakeries and equipment manufacturers. Traditionally, an oven was a one-time capital expenditure (CapEx), with subsequent revenue for the manufacturer limited to sporadic sales of parts and service contracts. The new model, however, is built on a foundation of continuous data processing and cloud-based services, creating an ongoing, symbiotic relationship.

This begins with the recognition that the AI and cloud platforms, such as those developed by Bosch and AMF, have significant ongoing operational costs for the manufacturer in terms of data storage, processing, and algorithm development. To monetize this continuous value creation, manufacturers are shifting from being simple hardware vendors to becoming ongoing service providers. This is manifesting in the form of subscription-based services. AMF’s “Sustainable Oven Service (SOS)” and Middleby’s “Open Kitchen” platform are not just features; they are products in their own right. These services provide bakeries with recurring value in the form of predictive maintenance alerts, performance benchmarking against an anonymized industry average, and detailed energy optimization reports. For the bakery, this means a portion of the cost of their oven’s intelligence shifts from a one-time upfront payment to a recurring operational expense (OpEx). This has massive implications for financial planning and budgeting, requiring a move towards a blended CapEx/OpEx model for acquiring and operating key production assets. The innovation, therefore, is not just the AI in the machine, but the transformation of the entire industry’s value chain and business model.

Innovation 2: The Fully Integrated IoT Ecosystem (Industry 4.0)

While AI-powered ovens represent the intelligence within a single machine, the second major innovation for 2025 is the networking of all such intelligent equipment into a single, cohesive, and centrally managed system. This is the practical realization of the “Smart Bakery” or “Industry 4.0” concept: a production environment where every piece of equipment communicates, collaborates, and contributes to a holistic optimization of the entire plant. It moves beyond the era of siloed automation, where individual machines perform their tasks in isolation, to an era of integrated intelligence.

Core Technology

The integrated IoT ecosystem is built upon a software and hardware architecture that enables seamless communication and control across the entire production line. The first component is the centralized control platform. Software suites such as WP BakeryGroup’s WP BakeryControl, Grantek’s Smart Bakery Solutions, and AMF’s AMFConnect™ act as the plant’s central nervous system. These platforms provide a unified dashboard interface from which managers can supervise, control, and analyze the entire production flow, from raw material intake to final packaging.

The second, and most critical, component is inter-equipment communication. This is where the true power of the ecosystem is unleashed. In an integrated bakery, machines share data to proactively adjust their processes. For example, a smart mixer like the WP Kemper KRONOS completes a batch and communicates the precise dough temperature and development time to the proofer. The proofer, in turn, uses this data to adjust its own temperature and humidity settings to achieve the perfect proof for that specific batch. As the dough exits the proofer, a signal is sent to the AI-powered oven, which has already begun preheating to the exact temperature required, ensuring a seamless and optimized transition. This continuous, automated data exchange eliminates the gaps and potential for error that exist in a manually coordinated line.

The final layer is Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) integration. The most advanced platforms do not operate in a vacuum; they interface directly with the bakery’s core business software, such as SAP. This connection creates a complete, transparent digital thread. Production schedules on the plant floor are automatically aligned with real-time sales orders, raw material inventory levels, and shipping logistics. This enables full traceability, allowing a manager to track a single loaf of bread from the specific batch of flour it came from all the way to the truck it was loaded onto for delivery.

Key Players & Systems

The market for these integrated platforms is being shaped by both traditional equipment manufacturers and specialized system integrators:

- Grantek: This company stands out as a dedicated system integrator, offering a complete, vendor-agnostic Smart Bakery Solution. Their platform is designed to connect mixing, oven analytics, packaging, and warehousing systems, even if they are from different manufacturers, and overlay AI-powered predictive analytics for holistic plant management.

- WP Bakery Group: Their WP BakeryControl software is a proprietary platform designed to network their own ovens, loading systems, and mixers. It provides centralized control, recipe management, and can be connected for remote diagnostics.

- AMF Bakery Systems: The AMFConnect™ Smart Dashboard is the centerpiece of their integrated offering. It is designed to consolidate real-time operational data from all connected AMF equipment into a single, accessible interface to drive faster and more informed decision-making.

- Bühler Group: The Bühler Insights platform serves as their secure, high-performance cloud environment for hosting digital services. It allows customers to collect and analyze process data to identify trends, optimize machine settings, and improve overall efficiency.

Impact Analysis

The adoption of a fully integrated IoT ecosystem delivers benefits that are systemic in nature, transforming the entire operational and economic model of a bakery.

- Holistic Optimization and Throughput Amplification: By providing a complete view of the production line, these systems allow managers to identify and eliminate bottlenecks that would be invisible when looking at machines in isolation. The system can automatically adjust the speed of the entire line to match the capacity of the slowest process, ensuring a smooth, continuous flow and maximizing overall plant throughput.

- Proactive and Predictive Maintenance: A major source of lost revenue is unplanned downtime due to equipment failure. An integrated IoT ecosystem constantly monitors the health of every connected machine—tracking motor vibrations, energy consumption, and cycle times. By analyzing this data, the system can predict when a component is likely to fail and automatically schedule maintenance before the breakdown occurs, transforming maintenance from a reactive, costly fire-fight into a planned, proactive activity.

- Enhanced Traceability and Food Safety: In the event of a product recall, speed and accuracy are paramount. A fully integrated system provides an instantaneous and complete digital record of every batch. A manager can immediately identify which products were made with a specific lot of ingredients, which machines they were processed on, and where they were shipped. This capability is invaluable for meeting stringent food safety regulations and protecting brand reputation.

The widespread adoption of these integrated ecosystems is surfacing a critical strategic consideration for bakeries: the challenge of data standards and the integration of legacy equipment. A truly “smart” bakery requires all of its components to communicate seamlessly, but this is complicated by the reality of the factory floor.

Most existing bakeries are “brownfield” sites, operating a diverse mix of equipment from various manufacturers, purchased over many years. A new, state-of-the-art smart oven from WACHTEL must be able to exchange data with a ten-year-old mixer from a different brand. This presents a significant integration hurdle. Major equipment manufacturers like WP, AMF, and Bühler are developing powerful but often proprietary platforms, creating “walled gardens” where their own equipment works together perfectly, but connecting to third-party machines can be difficult or impossible.

This dynamic creates a crucial market opportunity for specialized system integrators like Grantek, whose primary value proposition is their ability to bridge these communication gaps, making disparate systems from different vendors and generations work together as a single, cohesive unit. It also signals a long-term push towards the adoption of open, industry-wide communication protocols, similar to the OPC Unified Architecture (OPC-UA) standard seen in other manufacturing sectors. The equipment manufacturers who are first to embrace open standards, allowing their machines to easily integrate into any ecosystem, may gain a significant competitive advantage over those who insist on closed, proprietary systems.

Therefore, the strategic question for a bakery executive in 2025 is not simply, “Which smart oven should I buy?” but rather, “Which digital ecosystem is this oven a part of, and how open and flexible is that ecosystem to integrate with the legacy and future equipment in my plant?”. The choice of platform is becoming as important, if not more so, than the choice of any single piece of hardware.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Smart Bakery Platforms

| Platform / System |

Core Functionality |

ERP Integration |

Architecture |

Key Differentiator |

| AMFConnect™ |

Real-time Monitoring, Predictive Maintenance (SOS), Energy Management |

Custom |

Proprietary |

Strong focus on oven performance and sustainability metrics through its Sustainable Oven Service (SOS). |

| Bühler Insights |

Process Data Collection, Trend Analysis, Digital Service Hosting |

Custom |

Proprietary |

Leverages Bühler’s deep expertise in grain and food processing to optimize processes from raw material to finished product. |

| WP BakeryControl |

Centralized Machine Control, Recipe Management, Remote Diagnostics |

Yes |

Proprietary |

Tightly integrates WP’s own line of mixers, loaders, and ovens for seamless process automation and control. |

| Grantek Smart Bakery |

Holistic Plant Integration, AI-driven Predictive Analytics, Warehousing |

Yes (SAP, etc.) |

Open / Vendor-Agnostic |

Specializes in integrating new and legacy equipment from multiple vendors into a single, unified control and analytics platform. |

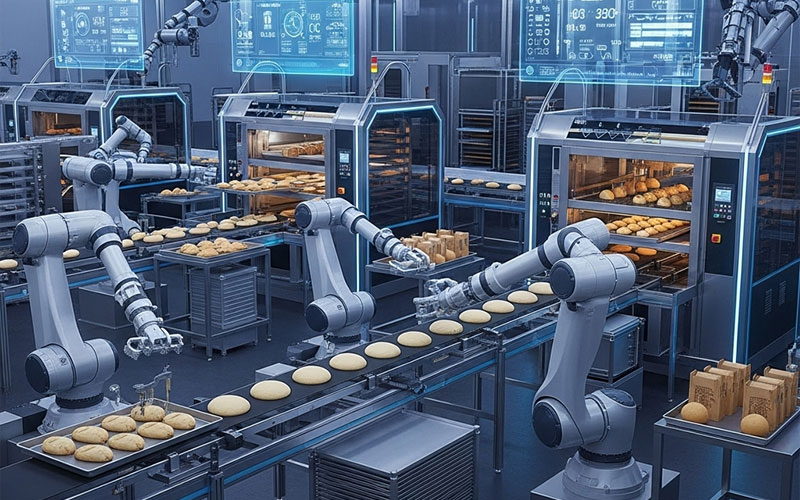

Innovation 3: Collaborative Robotics in Dough Handling & Packaging

The third pillar of the digital bakehouse is the deployment of advanced robotics, specifically collaborative robots or “cobots.” This trend marks a significant evolution from the large, caged, high-speed industrial robots of the past. Cobots are designed to work safely and effectively alongside human employees, taking over tasks that are repetitive, physically demanding, or require a level of precision and consistency that is difficult for humans to maintain over a full shift.

Core Technology

The effectiveness of modern bakery robots is driven by a convergence of hardware and software advancements. The first is the integration of advanced vision systems. Robots equipped with high-resolution 2D and 3D cameras, coupled with AI-powered image analysis software, can perform a wide range of tasks. They can conduct real-time quality control, inspecting finished products for size, shape, color, and topping distribution. They can also verify the accuracy of decorations and ensure the integrity of final packaging, all at speeds far exceeding human capability.

The second key technology is the development of gentle and adaptive end-effectors, more commonly known as grippers. Baking presents unique challenges for robotic handling; products can be fragile, sticky, irregularly shaped, or easily damaged. New grippers, often using soft robotics principles and vacuum technology, are being engineered to delicately handle everything from soft, high-hydration artisan doughs to intricately decorated pastries without causing damage or leaving marks.

Finally, force-sensitive robotics allows for greater adaptability in less-than-perfect environments. Older robotic systems required absolute uniformity and would halt if they encountered an unexpected variation. Modern robots, however, can sense and adapt. For example, they can adjust their grip to pick up a pastry from a tray that may be slightly dented or misaligned, a common occurrence in a busy bakery, thus preventing line stoppages and increasing overall system uptime.

Key Applications

Robotics are being deployed across the bakery production line to automate key processes:

- Dough Handling and Processing: This is a primary area for automation. Robots excel at the precise and consistent portioning, dividing, shaping, and molding of dough. They can form dough into countless shapes with a level of speed and weight accuracy that manual methods cannot replicate, ensuring uniformity and reducing waste.

- Icing, Decorating, and Finishing: Turnkey robotic cells are now available that can automatically ice and decorate cakes and other pastries. These systems can detect surface imperfections on a cake and adjust their application patterns to ensure a consistent, high-quality finish, with some systems capable of decorating up to 10 cakes per minute.

- Packaging and Palletizing: This is one of the most common and impactful applications. Robots can gently pick and place fragile baked goods into primary packaging, reducing the risk of damage and human contamination. They then take over the physically strenuous tasks of case packing (placing packaged goods into shipping boxes) and palletizing (stacking boxes onto pallets for shipment), eliminating a major source of ergonomic injuries for workers.

Impact Analysis

The strategic deployment of robotics provides a direct and powerful solution to some of the industry’s most acute problems.

- Solving the Labor Crisis and Improving Safety: Automation directly addresses the critical challenge of labor shortages and high employee turnover by taking over tasks that are repetitive, physically demanding, and often considered less desirable. A case study from a European bakery producing artisan bread at a rate of over three tonnes per hour demonstrated that the implementation of an automated mixing and bowl transport system reduced the required staffing for that part of the process from five operators down to just one. This not only cuts labor costs but also improves workplace safety by eliminating tasks that lead to repetitive strain and other ergonomic injuries.

- Accelerated ROI and Financial Viability: While the initial investment in robotic systems can be substantial, the financial returns are becoming increasingly attractive. The typical payback period for manufacturing automation has decreased dramatically, from 5-8 years in previous decades to just 1-3 years today. This rapid return is driven by a combination of factors: direct labor cost savings, significant increases in productivity (one case study noted a productivity jump of 70% in processing and nearly 280% in packaging ), and a sharp reduction in product waste caused by human error, which can account for as much as 23% of all production mishaps in a manual process.

- Enhanced Quality and Food Safety: Robotic precision guarantees a level of consistency in product size, weight, and shape that is unattainable with manual labor. This leads to a more uniform final product and a more predictable baking process. Furthermore, by minimizing direct human contact with the product, especially during the post-bake and packaging stages, robotics significantly enhances food safety and reduces the risk of contamination.

Table 3: ROI Model for a Fully Automated Mixing & Dough Handling System

| Item |

Description |

Calculation / Assumption |

Annual Cost / Savings |

| A. Initial Investment (CapEx) |

|

|

|

|

Robotic System & Mixer |

Cost of robotic arm, integrated mixer, and controls. |

($250,000) |

|

System Integration & Programming |

Cost for specialized integrator to design, build, and program the system for bakery-specific tasks. |

($150,000) |

|

Installation & Training |

On-site installation, commissioning, and staff training. |

($50,000) |

|

Total Investment |

|

($450,000) |

| B. Annual Operational Savings (OpEx Reduction) |

|

|

|

|

Labor Cost Reduction |

Reduction from 4 FTEs to 1 FTE for mixing/handling. Assumes fully burdened labor cost of $50,000/year per FTE. |

$150,000 |

|

Reduced Ingredient Waste |

15% reduction in waste from inconsistent portioning and handling errors. Assumes annual ingredient cost of $400,000 for the line. |

$60,000 |

|

Increased Throughput/Yield |

10% increase in effective yield due to higher consistency and reduced downtime. Assumes annual revenue from the line of $1,500,000. |

$150,000 |

|

Total Annual Savings / Added Value |

|

$360,000 |

| C. Payback Calculation |

|

|

|

|

Simple Payback Period |

Total Investment / Total Annual Savings |

1.25 Years |

| D. Notes & Assumptions |

This simplified model demonstrates the financial viability of automation. It uses a simple payback period calculation and does not account for the time value of money (TVM), depreciation, or tax benefits, which would be included in a full Net Present Value (NPV) analysis. The model is based on realistic industry benchmarks for labor, waste, and productivity gains. |

|

|

Despite the compelling ROI, a significant barrier to the widespread adoption of robotics in bakeries remains. The primary challenge is often not the cost of the robot arm itself, but the substantial cost and complexity associated with system integration. A bakery producing a diverse portfolio of twenty different pastry types requires a highly flexible and sophisticated automated system. The engineering effort required to program the robots and to design, test, and source a variety of end-effectors capable of handling this wide array of shapes, sizes, and dough consistencies can be immense and costly. This “hidden cost” of integration can often exceed the price of the hardware, making the business case challenging for smaller bakeries or those with highly varied, small-batch production runs.

This integration challenge is, in turn, driving innovation in the market. It is fueling the development of turnkey, pre-integrated robotic solutions designed for very specific bakery tasks, such as the self-contained cake decorating cell mentioned in industry analyses. It is also accelerating the growth of alternative financing models, such as Robotics-as-a-Service (RaaS) and comprehensive leasing options. These models transform a large, prohibitive capital expenditure into a predictable, manageable monthly operational expense. This makes advanced automation financially accessible even for bakeries operating on tight margins, allowing them to realize the productivity benefits immediately. Consequently, the future of bakery robotics will be defined less by the hardware itself and more by the software, integration platforms, and innovative business models that make this powerful technology flexible, adaptable, and affordable for the entire industry.

Part II: The Imperative of Sustainable & Efficient Production

This section shifts focus from the digital and data-driven aspects of the modern bakery to the physical realities of resource consumption. The innovations explored here are direct responses to the powerful dual pressures of rising operational costs—particularly for energy—and the growing global demand for environmentally responsible manufacturing. These technologies are designed to plug efficiency leaks, reduce carbon footprints, and ensure compliance with an increasingly stringent regulatory landscape.

Innovation 4: Hybrid & Hydrogen-Fueled Thermal Systems

The heart of the bakery, the oven, is also its most energy-intensive component and a primary source of carbon emissions. The drive for sustainability is pushing manufacturers to fundamentally rethink how ovens are powered, leading to the emergence of flexible, future-proofed thermal systems that move beyond a reliance on a single fossil fuel.

Core Technology

Two primary technologies are leading this charge. The first, and more immediately accessible, is the hybrid oven. These systems are engineered with the flexibility to operate on multiple fuel sources, most commonly natural gas and electricity. An intelligent control system allows the oven to automatically switch between the two based on a variety of factors, such as real-time energy pricing from the utility, overall grid demand, or the specific heating profile required for a particular product. This capability not only provides a powerful tool for cost management but also significantly reduces idle energy waste and enhances operational resilience in the face of potential fuel supply disruptions. The Bühler Group, for instance, has already introduced hybrid-electric/steam deck ovens specifically designed to improve energy efficiency by a target of 20%.

The second, more revolutionary technology is the development of hydrogen-fueled burners. This represents a direct path to near-total decarbonization of the baking process. These systems replace traditional natural gas burners with advanced burners designed to run on clean-burning, renewable hydrogen. AMF Bakery Systems is a pioneer in this space with its Multibake™ Vita Tunnel Oven. This oven utilizes hydrogen-fueled burners and makes the remarkable claim of reducing CO2 emissions from the baking process by up to 99.9%. This technology effectively eliminates the oven as a source of direct carbon emissions.

Key Players & Systems

The development of these next-generation thermal systems is being led by major global equipment manufacturers:

- AMF Bakery Systems: Their Multibake™ Vita Tunnel Oven is a flagship example of a production-scale hydrogen-fueled system, signaling a clear commitment to a decarbonized future for industrial baking.

- Bühler Group: The company is actively developing and marketing hybrid solutions, such as their hybrid-electric/steam deck oven, offering a pragmatic step towards greater efficiency and lower emissions.

- Multiple Manufacturers: The trend towards hybrid systems is widespread, with numerous companies expected to showcase hybrid gas/electric models at major industry trade shows like IBA and IBIE in 2025, highlighting the industry’s collective move in this direction.

Impact Analysis

The adoption of these advanced thermal systems offers significant strategic advantages, positioning bakeries to thrive in a carbon-constrained and economically volatile future.

- Pathway to Decarbonization: Hydrogen-fueled ovens provide a clear and direct route to achieving ambitious sustainability goals, including corporate commitments to Net Zero and compliance with Scope 1 and Scope 2 emission reduction targets. This is not just an operational benefit; it is also a powerful marketing and branding tool, appealing to a growing segment of consumers who actively prefer to purchase from sustainable and environmentally responsible companies.

- Operational Cost Hedging and Resilience: Hybrid ovens provide an invaluable hedge against the volatility of energy markets. As the prices of natural gas and electricity fluctuate daily, a bakery with a hybrid system can dynamically switch to the more cost-effective fuel source, optimizing operational costs in real-time. This flexibility also provides a crucial layer of operational resilience against potential fuel shortages or grid instability.

- Proactive Regulatory Compliance: These technologies are a direct response to, and a method for getting ahead of, the increasingly stringent environmental regulations being implemented in key markets, most notably the European Union. By investing in low- or zero-carbon baking technology, bakeries can ensure future compliance and avoid the potential costs and business disruptions associated with failing to meet new standards.

While the technology for hydrogen-powered ovens is proven and available, its widespread adoption faces a critical dependency that exists outside the bakery’s walls: the hydrogen supply chain. The oven technology, as demonstrated by AMF, is ready for deployment. However, the environmental benefit of these ovens is entirely contingent on the source of the hydrogen fuel.

The vast majority of hydrogen produced globally today is “grey hydrogen,” which is manufactured using natural gas as a feedstock in a process that itself releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide. Using grey hydrogen in a bakery oven offers no net carbon benefit compared to simply burning natural gas directly. The promised 99.9% reduction in CO2 emissions is only achievable with “green hydrogen,” which is produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy sources, such as solar or wind power.

The infrastructure for producing and distributing green hydrogen at an industrial scale is still in its infancy. It is currently more expensive than natural gas and is only available in specific geographic regions, often referred to as “green hydrogen hubs,” where there are strong government incentives and significant investment in renewable energy generation.

Therefore, the adoption of hydrogen ovens in the near term will likely be limited to large, well-capitalized industrial bakeries located in these specific regions. These early adopters will be making a long-term (10-20 year) strategic investment, betting on the continued development of the green hydrogen economy. For the average bakery in 2025, the more pragmatic and immediately accessible innovation is the hybrid gas/electric oven. It offers a tangible and immediate step towards greater energy flexibility, cost management, and emissions reduction, without the dependency on a still-developing external fuel infrastructure.

Innovation 5: Advanced Heat Recovery & Energy Management Systems

Baking is the single most energy-intensive process in a typical bakery, responsible for a staggering 35-45% of the entire facility’s energy costs. A significant portion of this energy is lost to the environment in the form of waste heat. The fifth key innovation for 2025 is a suite of technologies designed specifically to capture, reuse, and intelligently manage this thermal energy, plugging the financial and environmental leaks inherent in traditional baking operations.

Core Technology

This innovation encompasses three interconnected technological approaches. First is the implementation of integrated heat recovery systems. These are engineered solutions that capture the high-temperature waste heat from oven flue gases, which can exit the oven at temperatures between 180°C and 200°C. This captured thermal energy, instead of being vented into the atmosphere, is then transferred via heat exchangers to other processes within the plant. Common applications include pre-heating water for sanitation and cleaning, providing heat for dough proofers, or even contributing to the building’s space heating. Leading manufacturers are offering these solutions both as integrated features in new ovens and as retrofittable units for existing equipment. The WP RETHERM system, for example, can be added to the company’s existing ROTOTHERM rack ovens and MATADOR deck ovens, while Exodraft offers a similar smart add-on module for gas-fired rack ovens.

Second, intelligent energy management systems move beyond simple heat recovery to actively optimize the oven’s entire energy profile. These are sophisticated control systems, like the WACHTEL ENERGY MANAGER or Middleby’s AI-driven DemandSmart platform, that govern every aspect of the oven’s power consumption. They employ features like “Economy Mode,” which automatically reduces power consumption during idle periods between bakes, and “AC Guard Technology,” which limits the simultaneous power draw of multiple heating elements to avoid costly peak demand charges from the utility. These systems ensure that the oven only uses the precise amount of energy needed at any given moment.

Third, significant gains are being made through advanced insulation and construction. Modern ovens are being built with far superior materials and designs to minimize passive heat loss. The use of high-tech ceramic fiber insulation can reduce heat loss by as much as 40% compared to older materials. This is often combined with features like triple-insulated glass doors and improved door seal technology to ensure that the heat generated by the oven stays inside the baking chamber, rather than escaping to heat up the surrounding kitchen.

Key Players & Systems

This crucial area of innovation is a focus for nearly all major oven manufacturers:

- WP Bakery Group: Their RETHERM heat recovery system is a key feature for their MATADOR deck ovens and ROTOTHERM rack ovens, explicitly marketed as an energy-saving solution that can be retrofitted.

- WACHTEL: The company highlights its ENERGY MANAGER with eco function as a core technology for reducing consumption in its ovens, including the flagship ATLAS EVO 3 rack oven.

- Exodraft: This company specializes in smart, add-on heat recovery technology specifically for gas-fired rack and tunnel ovens.

- Revent: A cornerstone of Revent’s brand identity is the low total cost of ownership of its ovens, which is heavily based on their industry-leading energy efficiency, high heat retention, and short recovery times, with the company claiming potential energy cost savings of up to 40%.

Impact Analysis

The implementation of these energy-saving technologies delivers a clear and compelling return on investment.

- Significant and Direct Cost Savings: The financial impact is substantial and well-documented. A collaborative research project between Campden BRI and the Carbon Trust concluded that simply optimizing flue gas control through better management could reduce a typical commercial oven’s gas usage by nearly 5%. For an average site, this translated into annual savings of over £14,000, with a calculated payback period on the required equipment of just one to five years. More comprehensive systems from manufacturers like Revent claim even more dramatic savings of up to 40% on total energy costs. These are not marginal gains; they are significant, recurring savings that flow directly to the bakery’s bottom line.

- Essential for EU Ecodesign Compliance: For bakeries operating in or selling into the European Union, these technologies are becoming mandatory. The EU’s Ecodesign and Energy Labelling regulations (such as Regulation (EU) 66/2014 and 65/2014) establish strict Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) for ovens and other appliances. These regulations are designed to progressively eliminate the least efficient products from the market. Ovens equipped with advanced heat recovery and energy management systems are essential for achieving the higher energy efficiency ratings (e.g., A+ or better) required for compliance and market acceptance.

- Increased Productivity and Throughput: Energy efficiency is intrinsically linked to productivity. Ovens with superior insulation and high heat retention, as emphasized by Revent, have much shorter temperature recovery times after the door is opened for loading and unloading. This means the oven is ready for the next batch more quickly, reducing cycle times and increasing the total number of batches that can be baked in a shift, thereby boosting overall plant throughput.

The intense focus on energy efficiency is creating a robust business case for retrofitting existing equipment, which represents a significant market shift. Many bakeries operate with older ovens that are mechanically sound but highly inefficient by modern standards. The capital cost of a complete replacement can be prohibitive, creating a barrier to upgrading.

In response, companies like WP Bakery Group and Exodraft are explicitly designing and marketing their heat recovery technologies as modular, add-on systems that can be retrofitted to a bakery’s existing assets. The documented payback period of one to five years for such an investment makes it a highly attractive financial proposition. A bakery can capture a substantial portion of the energy savings offered by a brand-new oven for a fraction of the initial capital outlay.

This dynamic carves out a distinct and growing “retrofit market” for specialized energy-saving technologies. It allows technology providers to engage with a much broader customer base, not just those who are ready for a full-scale equipment replacement. For the bakery owner, this fundamentally changes the investment strategy. Instead of facing a single, massive, all-or-nothing decision to replace an oven, they can now adopt a more agile and capital-efficient, incremental approach. They can first invest in upgrading the energy efficiency of their current ovens to realize immediate cost savings, and then use those savings to help fund a full replacement in the future.

Table 4: EU Regulatory Compliance Checklist for Commercial Ovens

| Regulatory Area |

Governing EU Directive/Standard |

Key Requirement for 2025 |

Action Required / Verification Method |

| Energy Efficiency |

Regulation (EU) 66/2014 (Ecodesign) & Regulation (EU) 65/2014 (Energy Labelling) |

Must meet Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) and display a clear energy label. The A+++ to G scale is being phased in, eliminating the least efficient models. |

Check the official EU Energy Label on the appliance. For professional equipment, request the product fiche detailing the Energy Efficiency Index (EEI) from the manufacturer. |

| Machine Safety |

Regulation (EU) 2023/1230 (Machinery Regulation) |

All machinery must bear a CE Mark, indicating it meets essential health and safety requirements. This includes protection against mechanical, electrical, and thermal hazards. |

Request the EU Declaration of Conformity from the manufacturer. Verify the CE Mark is physically affixed to the product. Ensure the technical file is available for inspection. |

| Hygiene |

EN 1672-2:2005+A1:2009 (Food processing machinery – Hygiene requirements) |

Equipment must be designed and constructed to be easily and thoroughly cleanable, preventing microbial contamination and using food-safe materials. |

Verify with the manufacturer that the oven design is compliant with EN 1672-2. Inspect the equipment for smooth surfaces, rounded corners, and accessibility for cleaning. |

| Electromagnetic Compatibility |

Directive 2014/30/EU (EMC Directive) |

The equipment must not generate electromagnetic disturbances that would interfere with other electronic devices, and it must be immune to interference itself. |

The EU Declaration of Conformity should list compliance with the EMC Directive. This is part of the overall CE marking process. |

Innovation 6: Resource-Efficient Automated Cleaning (Waterless & Low-Water CIP)

One of the most significant hidden costs in any bakery operation is cleaning. Manual cleaning is not only a major consumer of labor, time, water, energy, and chemicals, but it is also a primary source of process variability and a critical food safety risk. The sixth key innovation is the widespread adoption of automated Clean-in-Place (CIP) systems, which are becoming increasingly sophisticated, resource-efficient, and data-driven.

Core Technology

Modern CIP systems are a far cry from simple spray washers. They are highly engineered, automated systems that manage the entire sanitation process with precision. The core technology involves automated, multi-stage cleaning cycles. A typical cycle, managed by a central PLC, will execute a pre-rinse to remove gross soils, a heated caustic wash to break down organic residues, an acid rinse to remove mineral deposits, a final sanitizing rinse, and a final water rinse. Leading providers like Solenis (which acquired Diversey’s food hygiene business) and Korutek offer highly configurable systems that can tailor these cycles with up to 50 different parameters, applying specific chemical concentrations and temperatures to different zones of the equipment as needed.

A central focus of this innovation is radical resource optimization. To combat rising utility costs and meet sustainability goals, modern CIP systems are designed to minimize the consumption of water, chemicals, and energy. Key features include large recovery tanks that capture, filter, and reuse detergent and rinse solutions for multiple cycles; high-efficiency plate-and-frame or direct steam injection heat exchangers to heat solutions quickly and effectively; and precise, automated chemical dosing systems that inject the exact amount of concentrate required, eliminating wasteful manual mixing. Diversey’s “Flexible CIP” system architecture, for example, claims to deliver cost savings of at least 30% on freshwater consumption and 25% on chemical consumption compared to less advanced designs.

The efficiency of water use is further enhanced by advanced spray technology. Traditional static spray balls are being replaced by high-impact rotary jet devices. These heads rotate and spray cleaning solutions at high pressure, providing far superior mechanical cleaning action and surface coverage while using significantly less water and time to achieve a better result. Finally, the process is underpinned by

data-driven validation and compliance. “Intelligent CIP” systems are now equipped with a variety of sensors (e.g., conductivity, temperature, flow rate) that continuously monitor the cleaning process. Platforms like Solenis’s CIPTEC analyze this data to validate that the cleaning cycle was performed correctly and achieved the required level of sanitation. This creates a complete, unalterable digital record for every cleaning cycle, which is invaluable for demonstrating compliance with food safety standards like BRC Global Standards and HACCP.

Key Players & Systems

The market for advanced CIP solutions includes specialized chemical and equipment providers:

- Solenis (incorporating Diversey): A global leader offering a comprehensive portfolio, from compact, mobile CIP units suitable for smaller production lines or bakeries, to large-scale, fully integrated “Flexible CIP” systems. Their offering is distinguished by their suite of data analytics platforms, including Intelligent CIP, CIPCheck, and CIPTEC, which provide process optimization and validation.

- Korutek: This company specializes in developing automated CIP systems specifically for challenging applications like spiral freezers, chillers, and coolers, where contamination risks from pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes are high. Their systems are designed to be retrofitted to existing equipment and are scalable to meet different hygiene requirements.

- Colussi Ermes: As part of the Middleby Corporation, Colussi Ermes is a well-known manufacturer of industrial washing systems for the bakery and food processing industries, providing another avenue for integrated solutions within a larger equipment ecosystem.

Impact Analysis

The business case for investing in automated CIP is compelling, delivering returns across multiple operational domains.

- Maximizing Production Uptime: The most immediate benefit is a significant reduction in cleaning-related downtime. A manual cleaning process that could take a team of workers several hours to complete can be performed faster, more effectively, and often overnight or between shifts by an automated system. This frees up valuable hours for production, directly increasing plant capacity and revenue-generating potential.

- Guaranteeing Food Safety and Consistency: Automation removes the element of human error from the critical cleaning process. A CIP system performs the validated cycle perfectly every time, ensuring that even hard-to-reach areas like the internal surfaces of pipes and hidden crevices in equipment are cleaned to the same high standard. This drastically reduces the risk of microbial contamination and product cross-contamination, providing a much higher level of food safety assurance.

- Driving Significant Operational Savings: The resource efficiency of modern CIP systems translates directly into recurring cost savings. By slashing the consumption of water, energy (for heating), and expensive cleaning chemicals, these systems reduce a bakery’s utility bills and operating expenses day after day, leading to a strong and predictable return on investment.

While the term “waterless CIP” is often used and is highly appealing from a sustainability perspective, its practical application in a bakery context requires nuance. For most bakery equipment that comes into contact with wet, sticky, or high-fat products like dough, aqueous cleaning solutions containing caustics and acids are essential for effectively breaking down and removing the organic and mineral soils.

The true innovation in this area, as demonstrated by the systems from Solenis/Diversey, is not the complete elimination of water, but rather making the water-based cleaning process hyper-efficient. This is achieved through intelligent recycling of solutions, precise chemical dosing, and the use of high-impact spray technology that achieves a better clean with less water.

Where the concept of “waterless” or “dry” cleaning becomes highly relevant is in the sanitation of equipment that handles dry ingredients, such as flour silos, hoppers, and mixers prior to the addition of liquids. In these applications, automated systems that use a combination of high-pressure filtered air, powerful vacuum systems, and mechanical brushing can be considered a form of “dry CIP.” These systems can effectively remove dry particulate matter without introducing any moisture, which is often a critical control point for preventing microbial growth.

The overarching trend, therefore, is not a move to a single “waterless” solution, but towards the implementation of holistic, hybrid cleaning strategies. A state-of-the-art bakery in 2025 will likely employ a combination of automated cleaning methods: a dry CIP process for its raw material handling and storage systems, and a highly efficient, low-water wet CIP process for its mixers, depositors, proofers, and ovens. The strategic decision for a bakery owner is to conduct a full sanitation audit and implement a comprehensive, resource-efficient strategy that applies the right type of automated cleaning technology to the right part of the production line.

Part III: Redefining Product Quality & Versatility

The final set of innovations focuses on the end product itself. Driven by consumer demand for higher quality, greater variety, and more sophisticated offerings, these technologies are enabling bakeries to produce premium, artisan-style, and challenging products with industrial-scale efficiency and consistency. They bridge the gap between the craft of the small baker and the demands of the mass market.

Innovation 7: In-Line NIR Spectroscopy for Real-Time Quality Assurance

The traditional model of bakery quality control is fundamentally reactive. It relies on operators taking periodic physical samples from the production line and sending them to an on-site or off-site laboratory for analysis. By the time the results come back indicating a problem—for example, incorrect moisture content or protein levels—a significant quantity of off-specification product may have already been produced, leading to costly waste or rework. The seventh key innovation, in-line Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, shatters this outdated model by providing continuous, non-destructive, real-time quality analysis directly on the production line.

Core Technology

NIR spectroscopy is an analytical technique that uses the near-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum. The core technology consists of NIR sensors that are mounted over or integrated into the production line, such as on a conveyor belt. These devices continuously shine a beam of near-infrared light onto the product as it passes underneath. Different molecules in the product (like water, protein, and fat) absorb and reflect this light at specific wavelengths. By analyzing the spectrum of the reflected light, the system’s software can instantaneously and accurately determine the product’s chemical composition.

This enables the real-time measurement of multiple critical quality parameters without ever touching or destroying the product. In a bakery context, NIR can be used to continuously monitor key attributes of dough, batter, or finished goods, including moisture content, protein levels, fat content, ash content, sugar levels, and even gluten development and color.

The technology is highly flexible and can be implemented in several ways. At-line systems involve an operator taking a sample and placing it in a nearby NIR instrument for a rapid analysis. More advanced in-line systems integrate the sensor directly into the process stream, providing a truly continuous flow of data. A specific example of this is the INLINER system from ScanRG, which is designed to capture 3D, color, and near-infrared data from baked goods on a conveyor belt at high speeds. This data is then fed back to the plant’s central control system, creating a live feedback loop for process control.

Key Players & Systems

The field of NIR spectroscopy for food applications includes both specialized instrument manufacturers and providers of integrated quality control solutions:

- Polytec: A key provider of inline NIR spectrometers specifically for the flour and milling industries. Their systems are used to provide real-time analysis of incoming grain and milled flour for critical parameters like moisture, protein, ash, and gluten, allowing for optimal blending and processing.

- ScanRG: This company offers both the INLINER for continuous, in-line quality control of finished baked goods and the BAKEMETER for rapid, offline quality checks, providing a comprehensive QC solution.

- Brabender and Anton Paar: While their advanced instruments like the ExtensoGraph (for dough extensibility) and ViscoQuick (for viscosity) are typically laboratory-based, they play a crucial role in the ecosystem. The detailed, precise data generated by these instruments is often used to build and calibrate the chemometric models that power the in-line NIR systems, ensuring their accuracy.

Impact Analysis

The integration of in-line NIR spectroscopy fundamentally changes the nature of quality management in a bakery, shifting it from a retrospective activity to a proactive, preventative one.

- Achieving Zero-Defect Production: The continuous stream of real-time data allows for immediate, automated adjustments to the production process. If an NIR sensor detects that the browning of cookies exiting the oven is slightly too light, it can signal the oven’s control system to increase the temperature by a few degrees. If it detects that the moisture content of the dough leaving the mixer is 0.5% too low, it can trigger an adjustment in the water addition for the next batch. This ability to intercept deviations as they happen prevents out-of-spec products from ever being made, which dramatically reduces product waste, minimizes the need for rework, and increases overall yield.

- Enabling Complex and Functional Formulations: The consumer demand for “better-for-you” products, such as gluten-free, high-fiber, or high-protein baked goods, presents significant production challenges. These formulations are often far less forgiving than traditional recipes; precise control over ingredient ratios and moisture content is absolutely critical to achieving the desired texture and shelf life. In-line NIR provides the granular, real-time data needed to manage these sensitive formulations with the consistency required for large-scale production.

- Enhancing Food Safety and Brand Protection: Beyond compositional analysis, NIR technology can serve as an additional layer of food safety protection. It can be used to detect certain foreign material contaminants and can even be calibrated to infer potential microbial contamination based on subtle changes in the product’s chemical signature. This provides an early warning system that helps prevent unsafe products from ever reaching consumers, safeguarding public health and protecting the bakery’s brand from the devastating financial and reputational consequences of a product recall.

The true transformative potential of in-line NIR spectroscopy is realized when it is not used merely as a monitoring tool, but as an integral part of a closed-loop, autonomous control system. This represents the pinnacle of the “Smart Bakery” concept.

The process begins with the in-line NIR sensor generating a continuous, high-fidelity stream of quality data. This data is then fed directly into the control system of an AI-powered piece of equipment, such as a smart oven or an intelligent mixer. The crucial final step is the creation of a “closed loop,” where the output from the sensor directly and automatically informs the equipment’s actions, with no human intervention required.

A practical example illustrates this powerful synergy: An NIR sensor positioned after the mixer continuously measures the moisture content of the dough sheet. It detects that, due to a variation in the latest batch of flour, the dough’s moisture content is running 0.5% below the target specification. This data is instantly transmitted to the mixer’s AI-enabled controller. For the very next batch, the controller automatically calculates and adjusts the water addition by the precise amount needed to compensate for the flour variation and hit the exact moisture target.

This creates a self-correcting, self-optimizing system. It not only ensures absolute consistency in the face of raw material variability but also builds a sophisticated data model over time, learning the precise relationships between ingredient inputs and final product characteristics. This moves the bakery’s operation from simple monitoring to intelligent, autonomous quality assurance.

Innovation 8: High-Yield Soft Dough Processing Lines

One of the greatest paradoxes facing the modern industrial bakery is the soaring consumer demand for “artisan” products. These products—ciabattas with an open, airy crumb; baguettes with a crisp crust; breads made with high-hydration, slow-fermented doughs—derive their desirable characteristics from doughs that are notoriously soft, sticky, and difficult to handle. The eighth key innovation is the development of specialized production lines engineered specifically to manage these challenging doughs, allowing bakeries to replicate true artisan quality at an industrial scale and efficiency.

Core Technology

Traditional industrial dough handling equipment is often designed for stiffer, lower-hydration doughs and can impart significant stress, tension, and compression, which destroys the delicate gluten structure required for an open, artisan-style crumb. The new generation of soft dough lines is built on a philosophy of gentle handling. A prime example of this is the “SoftProcessing©” technology developed by FRITSCH. This system employs a series of specialized components, including a Soft Dough Sheeter (SDS) and a Soft Dough Roller (SDR), which are based on well-known satellite head technology but have been re-engineered to handle the dough with minimal pressure. This preserves the gas bubbles and delicate structure developed during fermentation, ensuring a light, open texture in the final product.

The gentle handling extends throughout the line with stress-free transfer mechanisms. Instead of being pulled or pushed, the dough sheet is moved between process steps using synchronized guillotines and innovative “omega drives” that relax the conveyor belt, avoiding any unnecessary stretching or jamming that could de-gas the dough.

A further key technological advance is the move towards oil-free processing. Traditional dough dividers and sheeters often rely on a thin film of oil to prevent the sticky dough from adhering to the machinery. However, this oil can affect the final product’s taste, appearance, and, crucially, its “clean label” status. The FRITSCH SDS system addresses this by using a clever system of fold-up conveyor belts that gently flour the dough sheet from all sides. This provides a natural, non-stick surface, eliminating the need for processing oils and allowing for a cleaner ingredient declaration.

Key Players & Systems

This specialized equipment niche is dominated by European engineering firms with deep expertise in dough rheology:

- FRITSCH (a member of the MULTIVAC Group): FRITSCH is the clear market leader in this segment. Their IMPRESSA bread line is the flagship industrial system, designed for high-volume production of top-quality artisan bread and capable of processing extremely soft, high-hydration doughs with high weight accuracy. For mid-sized retail bakers looking to scale up their artisan production, FRITSCH offers the

PROGRESSA bread line, which incorporates much of the same gentle handling technology in a more compact footprint.

- RAM SRL: This Italian manufacturer has carved out a reputation for specializing in high-performance dough processing machinery, particularly dividers, rounders, and moulders that are specifically designed to handle specialty and high-hydration doughs with precision.

Impact Analysis

The development of high-yield soft dough processing lines provides a direct technological solution to a major market trend, enabling significant commercial and operational benefits.

- Meeting Surging Market Demand: This technology directly empowers large-scale bakeries to tap into the rapidly growing and highly profitable market for premium, authentic, and artisan-style bakery products. It allows them to produce items like ciabatta, rustic rolls, and high-quality baguettes at an industrial scale, meeting the demand from retail and foodservice channels that they previously could not service efficiently.

- Superior and Consistent Product Quality: The gentle handling philosophy translates directly into a higher-quality final product. Breads produced on these lines exhibit better volume, a more desirable open and irregular crumb structure, and a better texture than those produced on conventional, high-stress lines. The automation inherent in the system also ensures high weight accuracy and consistent shaping, which is critical for packaging and slicing operations downstream.

- Significant Waste Reduction: The precision of the sheeting process is a key advantage. Systems like the FRITSCH SDS produce a highly uniform dough sheet with extremely well-defined edges. This minimizes the amount of scrap dough that needs to be trimmed from the sides of the sheet, reducing ingredient waste and improving the overall yield of the process.

The emergence and refinement of soft dough processing technology is a clear illustration of market pull driving technological innovation. It is a technology that was created specifically to solve a problem generated by evolving consumer preferences.

The causal chain is clear. First, consumers in developed markets began to show a strong and growing preference for “artisan” bakery products. They associate these items with higher quality, more authentic production methods, and healthier, simpler ingredient lists, and they have demonstrated a clear willingness to pay a premium for them.

Second, the defining characteristic of many of these artisan products is their use of soft, sticky, high-hydration doughs, which are notoriously difficult to handle with traditional, high-stress industrial equipment designed for stiffer doughs. Attempting to process these doughs on conventional lines results in poor quality, while relying on manual, craft-based production is not scalable enough to meet mass-market demand.

Third, this was compounded by the parallel rise of the “clean label” movement. This trend pressured bakeries to remove functional additives like dough conditioners and processing aids, including the divider oils commonly used to help manage sticky doughs in automated systems. This made the mechanical handling of these doughs even more challenging.

This confluence of factors created a clear and urgent market need: a technology that could automate the processing of difficult, high-hydration, “clean label” doughs without sacrificing the very artisan characteristics that consumers were demanding. Equipment manufacturers like FRITSCH responded directly to this need by engineering solutions like the IMPRESSA line, with its “SoftProcessing©” technology that is explicitly designed to be gentle on the dough structure and to eliminate the need for processing oils. This is a textbook case of consumer trends creating a specific industrial problem that was then solved through targeted technological innovation.

Innovation 9: Modular, Multi-Zone Deck & Combination Ovens

While industrial bakeries focus on scaling up production of specific items, a large and growing segment of the market—including in-store bakeries, high-street artisan shops, and foodservice operations—thrives on flexibility and variety. For these businesses, the ninth key innovation is the rise of modular, multi-zone, and combination ovens. These systems are designed to provide maximum baking versatility from a minimal physical footprint, allowing smaller operations to produce a diverse range of high-quality products without the space or capital for a full bank of specialized ovens.

Core Technology

This innovation is characterized by three key design principles. The first is a truly modular design. Ovens are constructed as individual, self-contained units or decks that can be stacked vertically or expanded horizontally as a business grows. This modularity offers significant logistical advantages; the individual modules can often be disassembled to fit through standard-sized doorways, which is a critical feature for installation in existing buildings or tight urban retail spaces where access is limited.

The second principle is the use of independently controlled baking zones. In a modern multi-deck oven, each deck is effectively its own separate oven. Each has its own heating elements, temperature controls, and often its own steam injection system. Crucially, the top and bottom heat within each deck can be adjusted separately. A prime example is the WACHTEL INFRA series of electric deck ovens. As the manufacturer notes, the number of individual baking chambers corresponds to the maximum number of different bakery products that can be produced at the same time. A baker can have one deck set at a high temperature with strong bottom heat for baking pizza directly on the stone, while the deck above it is at a lower temperature with gentle top heat and steam for baking artisan bread, and a third deck can be baking delicate pastries.

The third and most advanced principle is the combination oven. These units take flexibility a step further by integrating different types of baking technology into a single, cohesive appliance. A standout example is the Dibas blue2 PICCOLO C, a system co-developed by WIESHEU and WACHTEL. This unit combines a high-performance convection oven (ideal for products like croissants and cookies) with a stack of up to three true deck ovens (ideal for artisan breads and pizzas) in one space-saving footprint. This allows a bakery to leverage the benefits of both air circulation and radiant heat without purchasing two separate machines.

Key Players & Systems

This innovation is being driven by manufacturers who specialize in equipment for artisan, in-store, and foodservice bakeries:

- WACHTEL & WIESHEU: Their collaboration on the Dibas blue2 PICCOLO C combination oven is a leading example of integrating multiple baking technologies into one flexible unit. WACHTEL’s own

INFRA series of electric deck ovens exemplifies the principle of modularity and individually controllable decks.

- MIWE: The MIWE condo is a highly regarded modular deck oven. It is available in a wide range of sizes and configurations, and it features separately adjustable top and bottom heating, as well as an independent, dedicated steam device for each individual deck, providing ultimate control and versatility.

- Sveba Dahlen: Their D-Series deck oven showcases another aspect of smart, space-saving design by integrating a proofing cabinet directly into the oven’s base, optimizing both fermentation and baking within a single footprint.

Impact Analysis

The adoption of modular and combination ovens provides smaller-scale bakeries with the tools they need to compete effectively and respond to market trends.

- Enabling Product Diversification: The primary benefit is the ability to produce a wide and varied range of products from a single piece of equipment. This allows bakeries to directly address the consumer demand for greater variety and to experiment with new products without a major capital investment. They can offer fresh-baked bread, pastries, cookies, and even pizza, all from one oven system, maximizing their revenue potential per square foot.

- Optimizing Space and Energy Efficiency: In a retail or small bakery environment, floor space is a premium asset. These compact, vertically-oriented systems maximize production capacity from the smallest possible footprint. They also offer significant energy savings. The ability to switch on and heat only the specific decks that are needed for a particular bake, while leaving the others off, is far more efficient than running a large, single-chamber oven to bake a small batch of product.

- Providing Scalability and Investment Flexibility: The modular nature of these systems allows a bakery to grow over time. A new business can start with a smaller, more affordable two- or three-deck configuration. As the business succeeds and demand increases, they can simply add more modules to expand their capacity, making the initial investment less risky and more manageable.

The development of modular and combination oven technology is a critical enabler of the “hyper-local” and “in-store bakery” business models, which have become powerful forces in the food retail landscape. These models cannot compete with large industrial bakeries on the basis of price or volume for a single product. Instead, they compete on the promise of ultimate freshness, product variety, and the sensory appeal of “baking theatre”—the sight and smell of products being baked fresh on-site.

This business model has unique equipment requirements. A massive tunnel oven, the workhorse of industrial production, is completely impractical and inefficient for producing small batches of many different items throughout the day. Conversely, purchasing a separate specialized oven for each product category (one for bread, one for convection pastries, one for pizza) is prohibitive in terms of both capital cost and the physical space it would occupy in a high-value retail or kitchen environment.

Modular, multi-zone, and combination ovens, such as the MIWE condo or the WACHTEL/WIESHEU combination unit, represent the perfect technological solution to this specific business problem. A single oven footprint can be dynamically reconfigured throughout the day to meet changing demand. It can produce croissants and muffins in the morning using convection heat, bake artisan sourdough loaves at midday using intense deck heat and steam, and then switch to producing flatbreads or pizzas for the evening crowd using high bottom heat. This innovation is, therefore, more than just an improvement in oven design; it is a fundamental piece of infrastructure that underpins the operational and economic viability of the entire growing sector of in-store and high-street artisan bakeries.

Innovation 10: High-Speed Vacuum Cooling Technology

In a traditional bakery production line, the cooling stage is often a passive, time-consuming, and space-intensive bottleneck. After exiting the oven, baked goods must sit on large, multi-tiered racks for an extended period—sometimes hours—to cool down to a temperature suitable for slicing and packaging. The tenth key innovation, vacuum cooling, completely upends this process, using applied physics to dramatically accelerate the cooling step, which in turn unlocks significant gains in throughput, space utilization, and even product quality.

Core Technology

Vacuum cooling operates on the principle of lowering the boiling point of water by reducing atmospheric pressure. The core of the technology is a robust, sealed vacuum chamber into which freshly baked products are loaded. Once the chamber is sealed, powerful pumps rapidly evacuate the air, causing the pressure inside to drop significantly. As the pressure falls, the boiling point of the water within the hot product also drops dramatically. The residual moisture inside the bread or pastry flashes into steam at a much lower temperature than it would at normal atmospheric pressure. This phase change from liquid to gas (evaporation) is an endothermic process that rapidly draws thermal energy out of the product, cooling it from the inside out. This entire process can reduce product cooling times by an astonishing 90% or more, turning a process that took hours into one that takes mere minutes.

A crucial aspect of this technology is its ability to “finish” the bake. Because the vacuum cooling process itself removes a significant amount of moisture and helps to set the product’s internal structure, the initial baking time in the oven can be reduced. Instead of baking a loaf to a final core temperature of 94-96°C, it can be removed from the oven earlier, as soon as it reaches a minimum safe core temperature (typically around 85°C). This is the temperature required to ensure full starch gelatinization and the inactivation of enzymes and common pathogens. The subsequent vacuum cooling process then removes the final amount of moisture and stabilizes the crumb structure, effectively completing the baking and stabilization process outside of the oven.

Key Players & Systems

While still an emerging technology in some segments, vacuum cooling is being commercialized by several key players and validated by leading research institutions:

- Research & Development: Campden BRI, a highly respected food science research organization, has conducted extensive research on the application of vacuum cooling to bakery products. Their work, funded by bodies like Innovate UK, has scientifically validated the technology’s benefits and established the critical process parameters for ensuring food safety and quality.

- WP Bakery Group: This major German equipment manufacturer has commercialized the technology with its VACUSPEED® High Power Vacuum Cooling System, offering it as part of its integrated production line solutions.

- Revent: The Swedish oven specialist also lists Vacuum Cooling as a key technology in its portfolio, indicating its importance as a complementary system to their high-efficiency ovens.

Impact Analysis